ToK Essay Titles (May 26) explained using paintings

In Today’s blog we’ll explore how the May 2026 Theory of Knowledge Essay titles can be understood through some of the more recognisable paintings in Madrid’s Prado Gallery.

Each artwork helps us visualise the key concepts behind the six essay prompts — from observation and interpretation, to context, quantification, and doubt.

Just to be clear — these are not real-world examples for your essays. They are ways of illustrating the ideas and themes at the heart of each question. If you’d like real-world examples, check out the short “mini videos” for each essay on the ToKToday YouTube channel.

I love art, and I love ToK, so I thought I’d bring the two together. If you’ve never been to the Prado, this might give you a glimpse of its wonders — and show how art can help us to better understand knowledge, whilst ToK can help us to better understand art.

Essay 1 — Observation, Flaws, and Intention

Prompt: “Observation is an essential but flawed tool. Does it matter in the production of knowledge?”

Painting: Francisco Goya – The Clothed Maja and The Nude Maja

Francisco Goya, The Clothed Maja (c.1800) and The Nude Maja (c.1800) – Museo del Prado, Madrid.*

Goya’s two Maja paintings invite us to think deeply about the act of observation itself.

Who is observing whom? Are we observing the Maja, or is she observing us? And under what conditions is observation acceptable?

When the Spanish Inquisition confiscated The Nude Maja for indecency, observation itself became a moral act — a knowledge tool under suspicion. If we see the paintings separately, we notice beauty and technique; together, we see flaws in our own gaze. The real flaw lies not in the act of observing, but in the intentions behind it.

Historically, these works were radical. Commissioned around 1800, possibly by Prime Minister Manuel Godoy, they were hidden from public view. Their concealment reveals how observation is shaped by power, propriety, and censorship — a vivid example of how knowledge itself can be controlled.

Essay 2 — Doubt, Certainty, and the Pursuit of Knowledge

Prompt: “Doubt is central to the pursuit of knowledge. To what extent do you agree?”

Painting: Hieronymus Bosch – The Garden of Earthly Delights (c.1490-1500)

Bosch’s surreal vision of paradise, pleasure and punishment – Museo del Prado.

Bosch’s triptych is a masterpiece of epistemic doubt.

Is it a moral warning or a celebration of creation? Every interpretation opens new uncertainty.

In ToK terms, Bosch shows that doubt is not paralysis but a stimulus for inquiry. There is no single truth in his garden — only the pursuit of it. Perhaps that’s what makes doubt so central to knowledge: it keeps the search alive.

Painted for a private palace rather than a church, The Garden of Earthly Delights was freed from doctrinal certainty. Its strange imagery predates Freud’s psychoanalysis by centuries, yet seems to anticipate it. The painting’s ongoing reinterpretation shows that knowledge evolves through questioning rather than closure.

Essay 3 — Conveyance, Structure, and Meaning

Prompt: “Does the way in which knowledge is conveyed determine its power?”

Painting: Diego Velázquez – Las Meninas (1656)

Velázquez’s philosophical masterpiece – Museo del Prado.

Velázquez’s Las Meninas turns painting into philosophy — it is ToK in oil on canvas.

We are inside the royal palace, watching the Infanta Margarita flanked by her maids of honour. To the left stands Velázquez himself; in the mirror at the back, we glimpse King Philip IV and Queen Mariana of Austria.

Because you, the viewer, occupy the couple’s position, the painting pulls you into its structure. Who holds the power — the painter, the subjects, or the observer?

Velázquez doesn’t merely depict reality; he re-orders it, showing that perception itself is communication. As McLuhan said, “the medium is the message.”

By inserting himself among the royal household, Velázquez elevated the artist’s role to thinker and mediator. The mirror, the gaze, and the spatial depth became lasting symbols of how power and knowledge are constructed through representation. Its power lies precisely in how it is shown.

Essay 4 — Context, Understanding, and Perspective

Prompt: “Can we only understand something to the extent that we understand its context?”

Painting: El Greco – The Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest (c.1580)

El Greco’s austere nobleman – Museo del Prado.

El Greco’s portrait radiates solemn dignity — but what does it mean? Faith, honour, penitence, identity?

Each interpretation depends on context: religious, social, or personal.

Understanding art, like understanding any knowledge, depends on the frameworks we bring. Without context, we may admire form but miss meaning. Yet context can also limit understanding by narrowing our interpretive frame. El Greco’s nobleman therefore asks: Do we ever truly know something itself, or only its reflection within our context?

Painted in Toledo during the Counter-Reformation, the gesture of hand-to-heart may signify devotion or status. Over time, the sitter’s identity has been debated, proving that context — lost or recovered — alters meaning. The very shifts in interpretation reveal that understanding itself evolves through changing contexts.

Essay 5 — Quantification, Harmony, and Expression

Prompt: “All things are numbers.” To what extent do you agree?

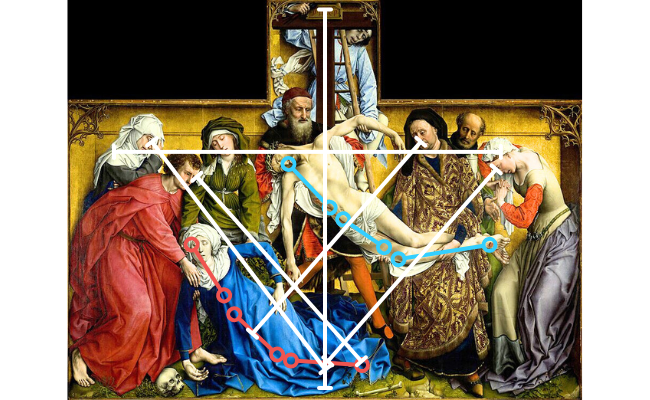

Painting: Rogier van der Weyden – The Descent from the Cross (c.1435)

Van der Weyden’s mathematical harmony and human emotion – Museo del Prado.

At first glance, van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross feels purely emotional and devotional. Yet the composition is mathematically balanced: Christ’s body mirrors Mary’s, diagonals form geometric harmonies reminiscent of Pythagoras.

Here, quantification creates beauty, but emotion gives it meaning.

Numbers bring structure, yet they cannot measure grief or faith. Perhaps not all things are numbers — but without numbers, even emotion might lack form.

Painted for the Crossbowmen’s Guild in Leuven, the work unites precision and pathos. Its proportional grids echo the Pythagorean idea of cosmic order, while its humanity — the Virgin’s faint, Christ’s weight — transcends calculation. Across centuries, its balance of geometry and empathy captures the tension between measurement and meaning that lies at the heart of this ToK prompt.

Essay 6 — Interpretation, Reliability, and Bias

Prompt: “In the production of knowledge, to what extent is interpretation a reliable tool?”

Painting: Francisco Goya – The Third of May 1808 (1814)

Goya’s condemnation of war – Museo del Prado.

Goya’s Third of May 1808 depicts a French firing squad executing Spanish civilians.

At the centre, a man in white opens his arms in surrender or martyrdom, illuminated by a single lantern — his pose recalling Christ on the cross.

The painting stages execution, martyrdom, and witness — but also interpretation. Is this history or protest, empathy or propaganda? Goya’s choices of light, gesture, and anonymity shape how we understand the event.

Interpretation gives meaning to knowledge, yet it also frames it. It can be both reliable and risky — revealing truth through subjectivity.

Painted after the French occupation ended, Goya’s work was among the first to condemn war rather than glorify it. He was not an eyewitness; his painting interprets testimony. Later governments alternately censored and celebrated it, showing how interpretation is bound to politics. The faceless soldiers and harsh light construct memory itself — a testament to the power and peril of interpretive knowledge.

In Summary…,

If you’d like more direct guidance on each of the May 2026 ToK Essay titles, watch the short videos on the ToKToday channel — there are three five-minute clips for each prompt.

I’ve only touched on the Prado’s treasures, but hopefully you can see that every painting there is a kind of visual essay on how knowledge is produced, interpreted, and understood. Colleagues may wish to do a similar exercise with their students in their local art gallery, or use films, music or television as the objects for explaining the essay titles.

Daniel, Lisbon, October 2025