Is AI Knowledge the Same as Human Knowledge?

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming how we think about knowledge and its production, making it an increasingly valuable topic for Theory of Knowledge (ToK) classrooms. The rise of generative AI tools such as ChatGPT raises profound questions about authorship, interpretation, and the nature of knowing itself. Can we treat AI-generated outputs as “knowledge” in the same way that we treat human knowledge? Or does AI create something fundamentally different, requiring us to rethink ToK’s core frameworks?

For ToK teachers, the debate over AI’s role as a knowledge producer provides a unique opportunity to help students critically examine key ToK concepts such as the influence of the knower, the role of the author, and the impact of tools and methods on knowledge. This blog explores how classic theories by Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault can be applied to AI, before considering arguments that AI knowledge is radically different from human knowledge.

Knowledge and the Role of the Producer

A basic principle of ToK is that the knowledge producer—whether an individual, a community, or an institution—shapes the knowledge that emerges. The producer brings their pre-existing knowledge, perspectives, intentions, tools, cultural context, and values, all of which influence the type and quality of knowledge produced. This is the “orthodox” ToK position: understanding knowledge requires us to examine the knower or author who created it.

However, as ToK students soon discover, this view can be reductive. The meaning of knowledge cannot always be distilled solely from the author’s identity or intent. To move beyond this simplified framework, we can draw upon critical philosophical perspectives, notably the work of Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault, who challenge conventional notions of authorship.

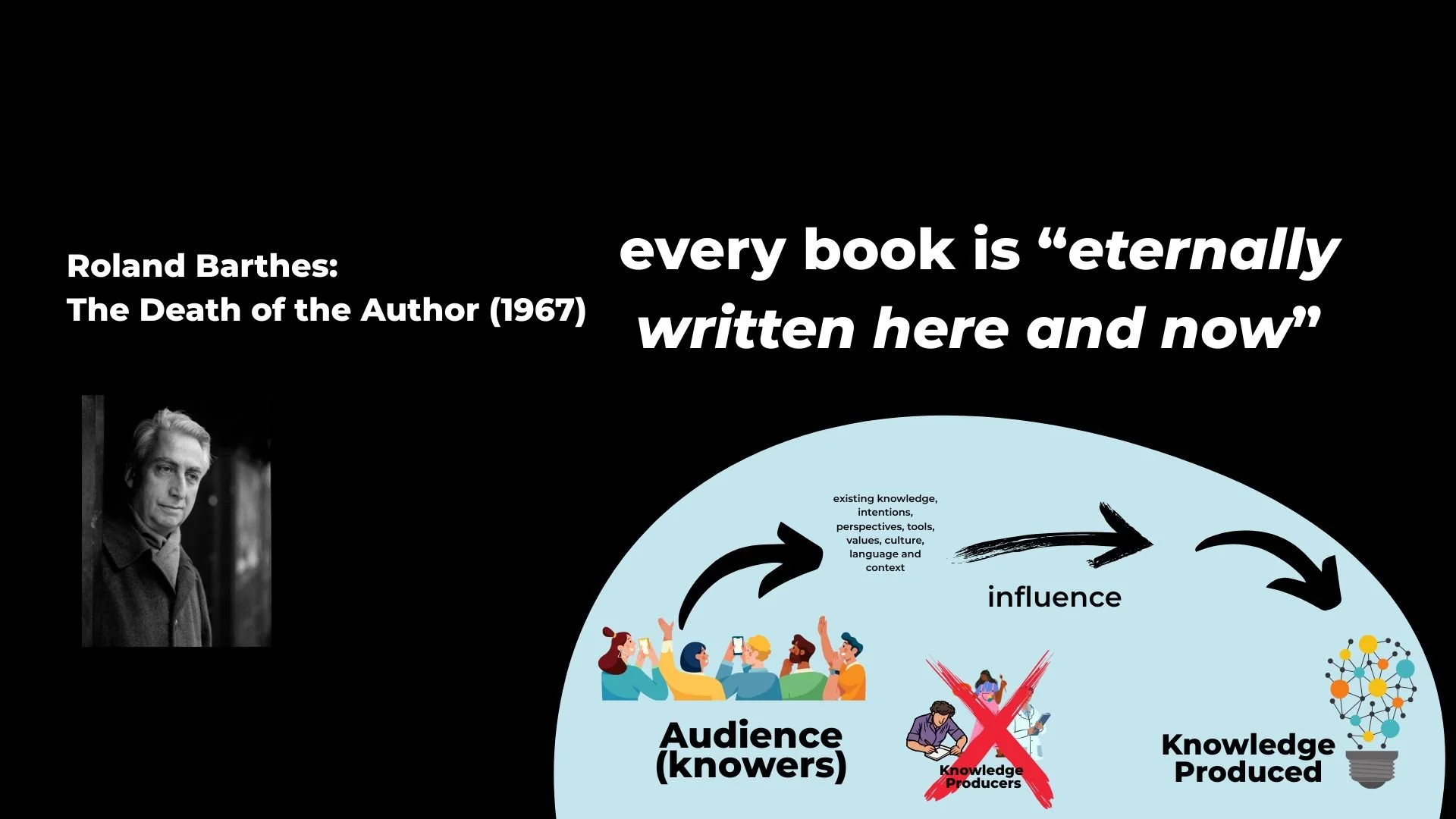

Barthes and the Death of the Author

In his influential 1967 essay The Death of the Author, Roland Barthes questioned the assumption that the meaning of a text (or knowledge) is tied to its producer. Barthes proposed that texts gain meaning not from their author but from their readers. The author is merely the scriptor—the person who provides a canvas upon which meaning is endlessly constructed and reconstructed by those who interpret it. As Barthes famously observed, every text is “eternally written here and now,” meaning that knowledge evolves each time it is encountered and reinterpreted by a new knower.

For ToK, this raises profound questions: if the meaning of knowledge resides with the audience, then perhaps the identity of the knowledge producer—whether Einstein, Darwin, or an AI system—is less important than the interpretations and uses of that knowledge by its knowers.

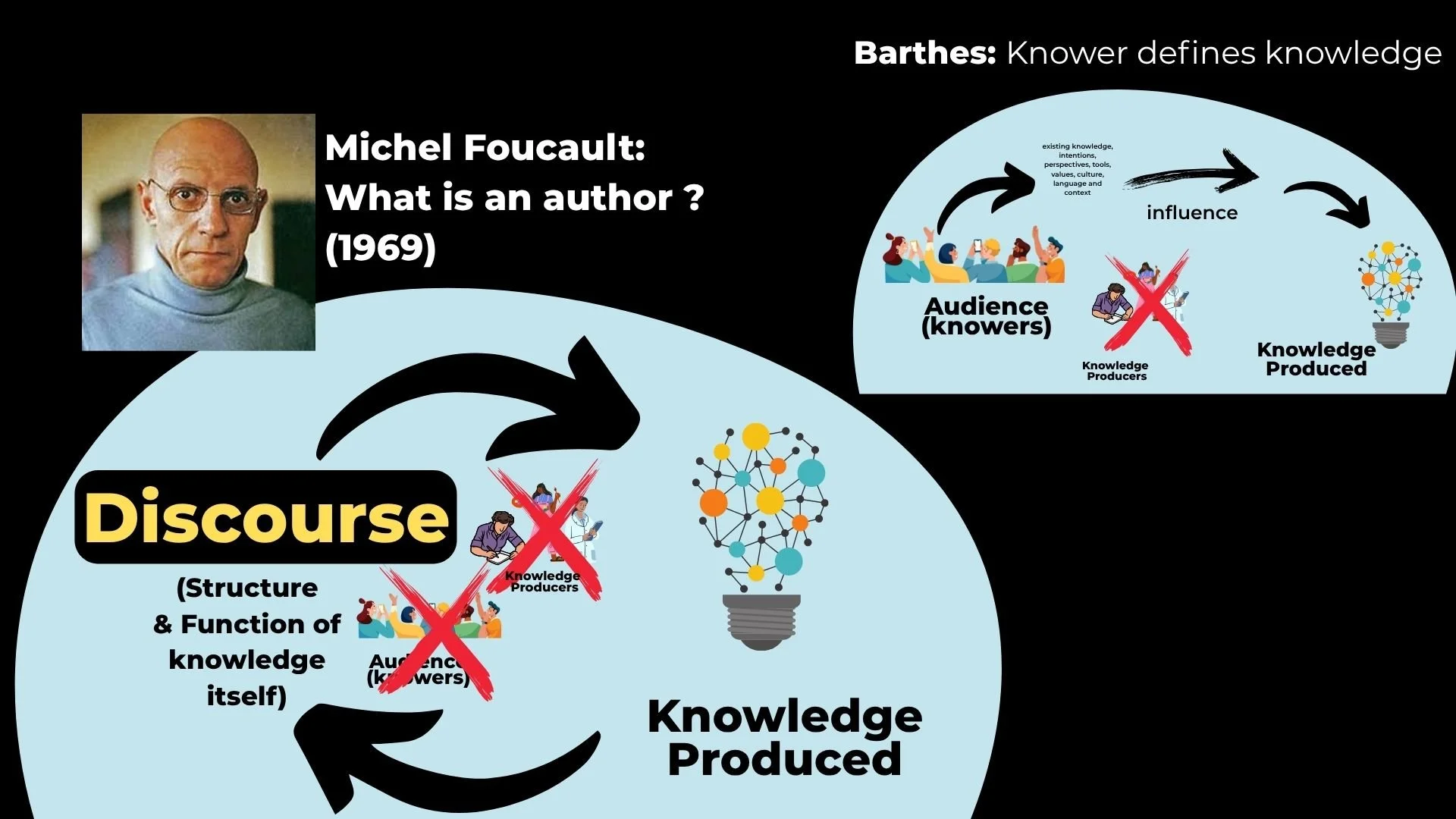

Foucault’s Author-Function and Discourse

Michel Foucault extended this critique in his 1969 lecture What is an Author?. Foucault argued that authorship is not a natural or fixed category but a social construct—a function of discourse. Discourse, in Foucault’s terms, refers to the structured systems of thought, practices, and institutions that regulate the production and circulation of knowledge in society. For Foucault, the “author” is a mechanism that limits and organises meaning, preventing the uncontrolled proliferation of interpretations.

Rather than focusing on the author’s personal intentions, Foucault suggests that we should examine the structures of knowledge itself and the discursive frameworks within which it operates. Applied to ToK, this perspective shifts our attention away from individual knowledge producers (human or AI) and towards the broader cultural and institutional forces that shape what counts as knowledge.

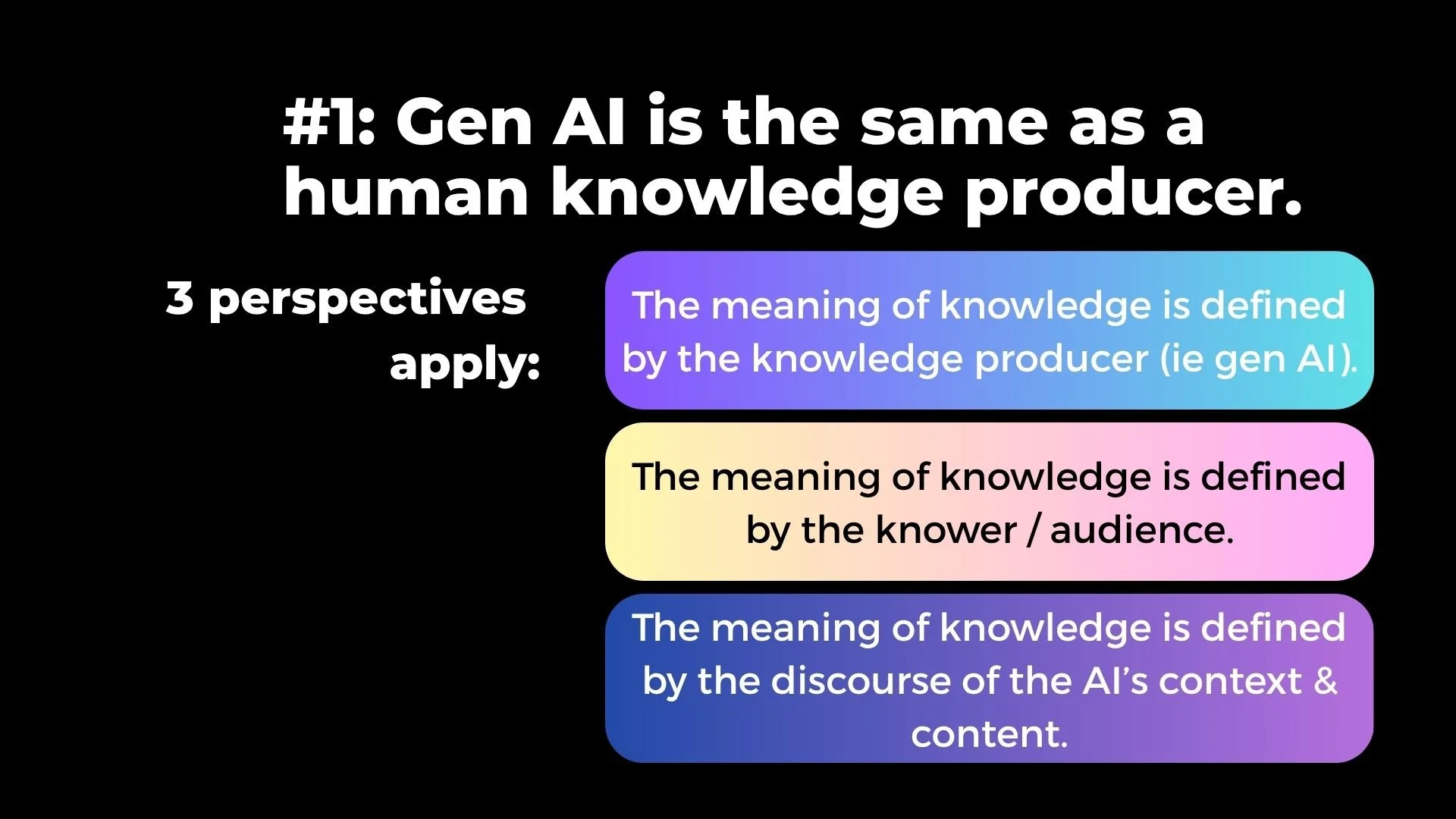

AI as Knowledge Producer: Conventional Views

When considering AI as a knowledge producer, the simplest approach is to treat it as analogous to human producers. From this viewpoint, AI-generated knowledge can be evaluated using the same frameworks that we apply to human-authored knowledge:

The AI system itself (or its developers and prompt engineers) could be seen as the “author” in Barthes’ sense.

Alternatively, following Barthes, we might argue that meaning is assigned by the human knower who interprets the AI’s outputs.

Or, as Foucault suggests, we could see AI knowledge as shaped by the discourses embedded in the training data, algorithms, and socio-technical structures that govern its production.

This argument treats AI as a sophisticated tool, comparable to earlier technological advances—such as the telescope, microscope, or printing press—that revolutionised the methods and tools of knowledge production. Like these tools, AI both extends and limits the forms of knowledge that can be pursued.

Is AI Knowledge Fundamentally Different?

A more radical argument is that AI produces a new kind of knowledge that is not equivalent to human knowledge. Philosophers such as John Searle (1980) argue that AI lacks intentionality and understanding—qualities central to human cognition. In his Chinese Room thought experiment, Searle demonstrates that a computer can manipulate symbols according to syntactic rules but does so without grasping their semantic meaning. AI systems, therefore, may generate convincing responses but lack genuine comprehension. This raises the question: can something be called “knowledge” if it is not accompanied by understanding?

Similarly, Miranda Fricker (2007) highlights the ethical and testimonial dimensions of human knowing in her work on epistemic injustice. Humans can be held accountable for their knowledge claims, whereas AI cannot. Shannon Vallor (2018) expands this argument, noting that AI systems lack the moral and intellectual virtues—such as honesty, humility, and courage—that underpin human epistemic practices.

Finally, Donna Haraway’s concept of situated knowledge (1988) underscores that all human knowledge is shaped by the knower’s lived experience and cultural context. AI, by contrast, is “disembodied” and detached from such contexts. While it can detect patterns and produce responses based on vast datasets, it cannot engage in first-person knowing or subjective interpretation. This calls into question whether AI outputs can be considered “knowledge” in the same sense as human knowledge.

Conclusion

In ToK, the debate over whether AI knowledge is the same as human knowledge opens up critical conversations about authorship, interpretation, and the tools of knowledge production. While we can analyse AI using established frameworks from Barthes and Foucault, the arguments of Searle, Fricker, Vallor, and Haraway suggest that AI-generated knowledge lacks the intentionality, moral agency, and situatedness that define human knowing. Whether this means we need to redefine what we call “knowledge” remains an open—and pressing—question.

Daniel, Lisbon, July 2025

References

Barthes, R. (1967). The Death of the Author. In Aspen, no. 5–6.

Foucault, M. (1969/1998). What is an Author? In J. Faubion (Ed.), Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology: Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984, Volume 2 (pp. 205–222). Penguin.

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford University Press.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599.

Searle, J. (1980). Minds, Brains, and Programs. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(3), 417–457.

Vallor, S. (2018). Technology and the Virtues: A Philosophical Guide to a Future Worth Wanting. Oxford University Press.